Large Scale: Lippincott Inc.

by Jonathan Lippincott

Before Lippincott, Inc. was founded in 1966, artists had no natural industrial partner and no capacity to produce sculpture on an industrial scale. They had to fabricate their own pieces, working alone or perhaps with assistants or students, or turn to manufacturers with no experience producing artworks. Sculpture was typically modest in scale, designed for intimate viewing, and often still produced in the artisanal manner—by the incremental labor of single artists.

Before Lippincott, Inc. was founded in 1966, artists had no natural industrial partner and no capacity to produce sculpture on an industrial scale. They had to fabricate their own pieces, working alone or perhaps with assistants or students, or turn to manufacturers with no experience producing artworks. Sculpture was typically modest in scale, designed for intimate viewing, and often still produced in the artisanal manner—by the incremental labor of single artists.

After Lippincott, Inc. was founded by my father, Donald Lippincott, and his business partner, Roxanne Everett, sculpture changed. It got bigger, it moved outdoors, it asserted itself as a modern form of public monument. The Lippincott shop introduced industrial production to sculpture and vice versa, and it helped create a new kind of work in which scale was not just a formal matter but a crucial part of the sculptural endeavor. Lippincott’s four decades in business correspond quite neatly with perhaps the most active period of public sculpture in art history; for more than a decade and a half, Lippincott was the only fabricator dedicated exclusively to fine art.

Many of the artists who came to Lippincott had not created sculpture in metal before, though they had worked extensively in other media (and often as painters as well). Lippincott fostered close collaboration between the artists and the crew, which allowed the company to act as an extension of the artists’ studios, and of their own hands. Usually, several different artists’ projects would be happening simultaneously, and in a way the shop served as a group studio space, far more elaborate than any one artist could possess. Lippincott worked with artists from the conception of a project to the completed sculpture, displayed these pieces in the field adjoining the shop, and installed the sculptures all over the country and the world. Work on a new sculpture began with discussions of the construction process, the final size of the piece, the engineering issues, and the building materials. Part of the discussion in planning each sculpture considered how the work would travel; most sculptures were made in elements that could be assembled and taken apart relatively easily, so that they could be moved from place to place.

Usually an artist would arrive with a model of some kind, either drawings or some small three-dimensional object. From this model, the artist and the crew would create templates for a piece to be executed at a large scale. The artist would usually need to make adjustments to allow for the change in scale, and artists were always encouraged to be directly involved in the process at every stage. Typically, an artist would review the progress of the sculpture several times during fabrication. The company’s proximity to New York City allowed them to make day trips as often as they liked, and some would come for several days at a time while their sculptures were being fabricated.

The photographs below document three major postwar artists—Barnett Newman, Louise Nevelson, and Claes Oldenburg—making work at Lippincott.

Barnett Newman’s Broken Obelisk, 1963–67, during installation for the show “Sculpture Downtown in Detroit,” 1969. The photo shows how the two elements of the sculpture fit together and how the junction bar, made of high-strength steel like that used in aircraft landing gear, projects up from the pyramid base.

Watching the final assembly of Broken Obelisk. Don stands next to the base, while Newman and his wife, Annalee, look on from the right side of the photo. The ropes attached to the top help guide the piece onto the junction bar.

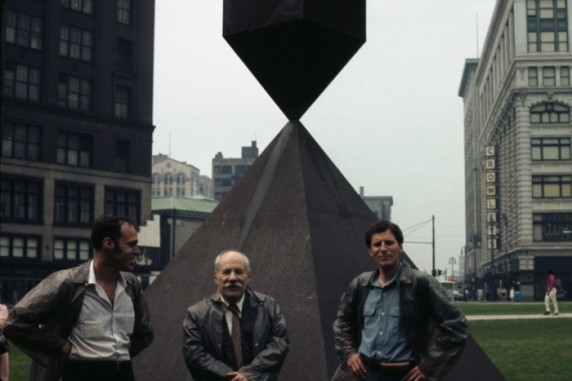

Don Lippincott, Barnett Newman, and Robert Murray (left to right) stand in front of Broken Obelisk. Newman and Murray were good friends, having met in Canada in the late 1950s, and it was Murray who first encouraged Newman to visit the Lippincott shop to consider working there.

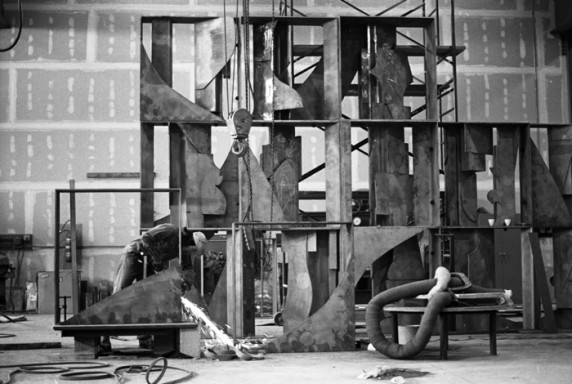

Louise Nevelson’s Sky Covenant, 1973, during fabrication at the shop. The interiors of the boxes were made individually, and the boxes were bolted together to assemble the completed sculpture. The worker at the lower left is grinding the edges of one of the interior components, so they fit together properly.

Sky Covenant during installation at the Temple Israel in Boston, which had commissioned the work.

Sky Covenant installed at Temple Israel. The sculpture is set out slightly from the facade, which creates an interesting play of light.

Claes Oldenburg’s Standing Mitt with Ball, 1973, during fabrication. The photo shows one step in the process of forming the quarter-inch weathering-steel shell of Mitt. This machine produces smooth, continuous curves by running the sheet of metal through rollers. Two initial rollers hold the sheet, and the third roller on the other side can be moved up and down to increase or decrease the diameter of the curve. Mitt is suspended from a crane, visible at the top of the photograph, which bears of the weight of the piece while the crew guides the shaping.

Laying out the ³/16″ lead sheet which will be the lining of Mitt. The lead sheet is resting on a bed of sand, which will support it during the forming process. The wooden ball of Mitt will be placed on the lead, and pressed into it to create the desired shape.

Placing the lead lining in the formed steel shell, which will act as a cradle during the move back into the shop for finishing.

Mitt with the lead interior and the wooden ball in place. The ragged edges of the lead are visible at the right side of the piece; these will be trimmed away as it is completed. Oldenburg is standing with Agnes Gund, who commissioned this sculpture.

Jonathan Lippincott is the design manager at Farrar, Straus and Giroux. He has worked as a book designer for seventeen years and lives in New York. Large Scale: Fabricating Sculpture in the 1960s and 1970s was published earlier this fall by Princeton Architectural Press.

Posted originally by the Paris Review, December 7, 2010

You must be logged in to post a comment.